Joseph Hauth

A Here's Tahuya Production

Joseph Hauth

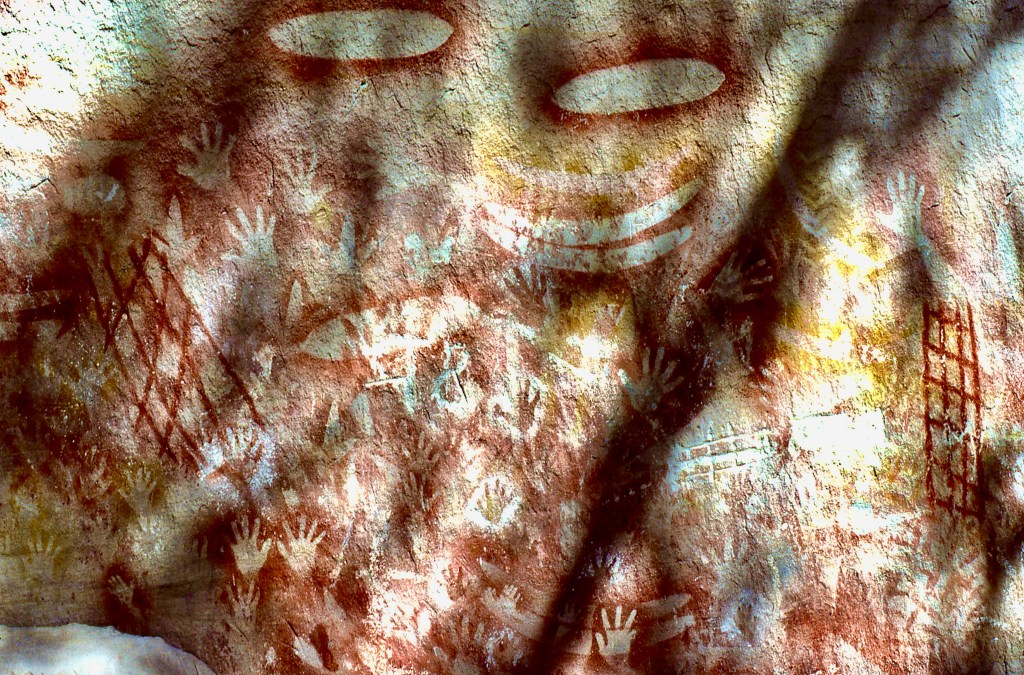

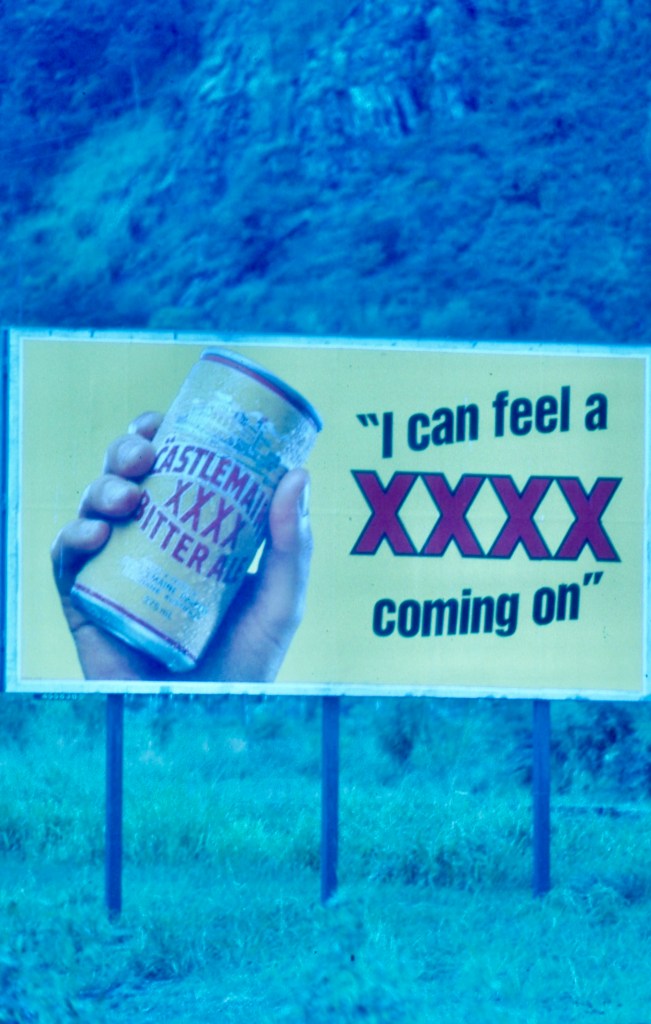

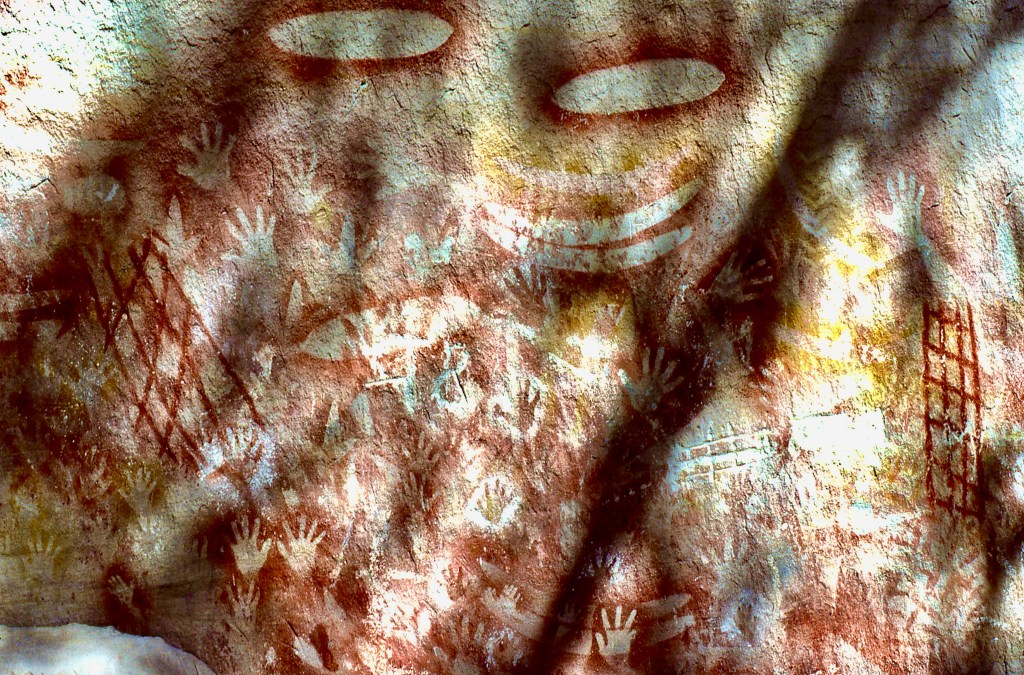

This recounting of the fable of the monkey of McMicken Island was recently told to me by Scooter McMicken, a resident of Herron Island and the great-great-great-great grandson of Jedidiah McMicken, who was the first to claim McMicken Island back in the 1800s. Rumored to be a summer getaway for Bigfoot family reunions, Jedidiah found several Bigfoot abandoned lairs, scattered with oyster and clam shells, along with some primitive cave art. Today the island is a state park and getaway for boaters, a perfect location for a vagabond monkey by the name of Humphrey. This is his story…

Humphrey was a very unlucky monkey, or was he?

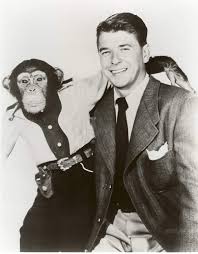

Humphrey was a very smart monkey, that’s for sure. He came from good primate research monkey stock. His research team could trace Humphrey’s lineage to Michael Jackson’s monkey, Bubbles, and even as far back as Ronald Reagan’s monkey, Bonzo.

So you knew when you met Humphrey there was something behind those eyes contemplating greater things for himself.

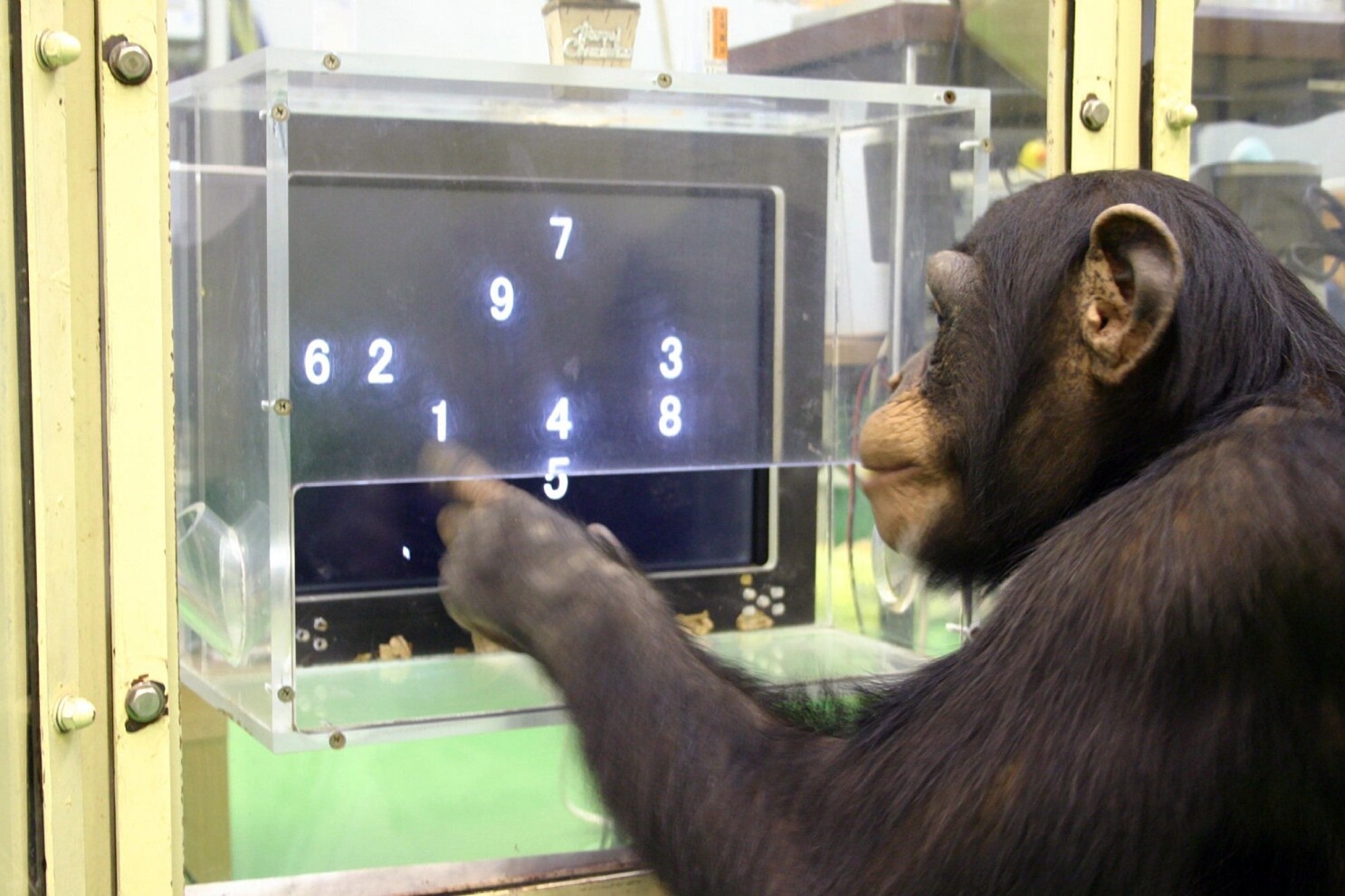

In the meantime Humphrey had to content himself with life at the University of Washington’s primate research laboratory. Great things were happening and he was the star of a research program that was on the very cusp of enabling chimpanzees to speak. It was very exciting times at the lab and the elite research team was breaking new ground.

You see, they were working closely with another research team at the university pioneering artificial intelligence. They had developed a process that, through computer algorithms taught to the chimpanzees, would allow the experimental chimps to speak perfect English. That is, if they could only get the chimpanzees to concentrate.

They had made great strides with Humphrey. He learned basic math as well, and was good with the money he received in the form of treats. And he even got pretty good at picking stocks in the stock market, usually involving bananas and other food item commodities.

Well, anyway, Humphrey (who, by the way, was named after Humphrey Bogart), just couldn’t seem to get the language down. Try as he might, Humphrey did not seem able to make the final revolutionary evolutionary leap forward to spoken language.

His research team hit on a new idea. “I’ve got it!,” exclaimed Dr. Dewey one day as Humphrey was reviewing stocks on his online trading account. “Let’s have him watch all his namesake movies, and his favorite actor, Humphrey Bogart.” “Well,”said Dr. Cheatham, “That just might get him to say a few movie lines at any rate.” “Agreed,” nodded Dr. Howe.

So they sat Humphrey down in the chimpanzee movie theater donated by the Institute for Simian Research in Sequim, Washington. This is where all the monkeys would watch Monday Night Football and Friday night movies together in between National Geographic and Hallmark films, which they loved. They would usually fling banana chips and apple slices at the screen when their favorite team was losing or if the movie was a dud.

Humphrey started watching the African Queen, Casablanca, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and well, frankly, just about any Bogart movie you can think of. To really help him think more about getting the words down, they bought him a fedora hat just like Bogart wore, although his was a bit less formal.

He really started getting into the role of Bogart and this greatly encouraged the research team. “Why, just look at him!,” exclaimed Dr. Rottweiler as she observed Humphrey one day pacing back and forth in the research lab’s two acre jungle which had been donated by the Foundation to Advance Chimpanzee Intelligence in Washtucna, Washington. Humphrey strolled along, sucking on his pipe in quiet contemplation, “I do believe he is starting to think he’s actually Humphrey Bogart!”

This continued on for several months until Humphrey had watched every Bogart movie multiple times. Aside from developing an obvious crush on Catherine Hepburn not a word was uttered from Humphrey’s mouth. He would do his computer labs with the artificial intelligence software, pick his stocks, work on math problems, but, alas, nothing was said.

Time was running out. The research grant (donated by the International Foundation for Monkey Freedom) was almost out of money because the nonprofit was cheap and Humphrey had refused to do an infomercial for them.

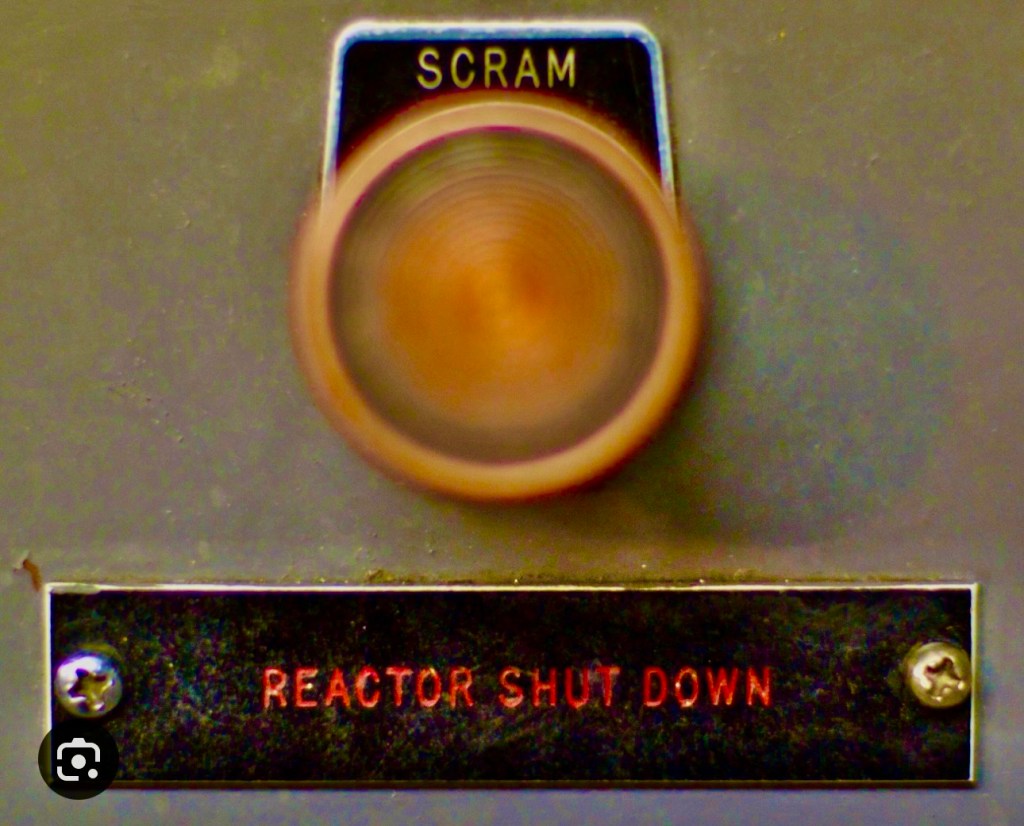

So finally the research team had to pull the plug on the project and recognize that Humphrey, as brilliant as he was, would not utter a word out loud even if his life depended on it. “It’s a shame,” said Dr. Rottweiler, tears running down her cheeks as she strolled with Humphrey through the garden on their way to the fully stocked cafeteria (donated by the wildly successful company allthingsmonkey.com). Humphrey nibbled on a banana and an apple and drank a smoothie while they sat by the artificial waterfall (donated by Gorilla Glue, Inc.), each lost in their own thoughts.

November was coming and it was time to donate Humphrey to an animal shelter or wildlife park. After much discussion, Drs. Dewey, Cheatham and Howe proposed to Drs. Rottweiler and Gottlieb that they donate Humphrey to the Olympic National Wildlife Refuge. There were all sorts of animals in the refuge, and Warren Harding’s great-grandson Biff, who was quite impressed with Humphrey’s approach to picking value-oriented stocks, agreed to build Humphrey his own special compound, replete with a cafeteria, movie theater, and Bogart-themed bedroom. The research team unanimously agreed that this would be best for Humphrey.

First they had to make sure that Humphrey would be well equipped for the trip to the wildlife refuge. They got him some rain gear, a backpack with camping supplies and food. Over a few evenings of excellent banana cream pies, lots of laughter, and Bogart movies, they prepared Humphrey for the long journey that lay ahead.

The rains came in November and it was particularly stormy on the day that they loaded Humphrey into the van along with Drs. Gottlieb, Rottweiler, Dewey, Cheatham and Howe. They all wanted to be along for the ride and make their final goodbyes to Humphrey, all wishing silently to each of themselves that he would actually say, “Goodbye.” Because then they would know he could speak and they could turn around and publish their findings and Humphrey would be famous.

But alas, it was not to be for the unlucky monkey. They drove south through Seattle in the pouring rain down to Tacoma, and then Olympia. Heading north up Highway 101 and then Highway 3 they continued in the driving rain and wind toward the refuge. Dr Cheatham had to use a restroom. They found a restaurant in a very deserted spot while the rain poured down, the windshield wipers on full speed, headlights stabbing the quickening darkness, and all around them black, dark, menacing forest.

“My God it’s desolate out here, isn’t it chaps?,” said Dr. Dewey. The doctors piled out of the van and ran into the restaurant to get out of the pouring rain and find the restroom and grab a bite for Humphrey. He was particularly fond of hot dogs and Diet Coke.

But Humphrey had other ideas. Grinning to himself he clambered out the back door, and in the pouring rain headed into the gloomy forest. He knew where he was going since he had been learning navigation skills and using his iPhone maps. Humphrey threw the backpack over his shoulders and pulled his slicker hood on tight. He had some walking to do.

Eventually working his way east he came to the bridge at Harstine Island. Black as the soul of hell itself, the rain pouring down, and the wind blowing ferociously up Pickering Passage, Humphrey leaned into the storm and crossed the bridge onto Harstine Island. No one was driving on such a motherless night and he made his way easily onto the island, stopping only here and there to get his bearings.

As daylight broke the rain and wind abated and he finally saw his destination, McMicken Island. The tide was high, so he sat down under the cover of a madrona tree on the beach and took a short rest. He breathed in the salty sea air and waited for the tide to go out.

After a nap he awoke to bright sunlight and sparkling water. McMicken Island beckoned him and with the tide now at low ebb he easily crossed the sandspit onto the island. There he found a state park and he moved quietly so the few boaters anchored at the state park would not notice him. He then began exploring the island. He knew from his research that this was an ancient Bigfoot holiday spot in days of old. As he explored further, he found what he was looking for; the best hideaway of all the Bigfoot creatures, Sir Sasqautch’s private den. It was very well hidden and he climbed down into the sanctuary and laid his gear down. This is where Humphrey would stay. Outside of the lair was a beautiful view looking east toward another island, Herron Island. Humphrey was intrigued because he could see cabins and people strolling the beach. He missed humans and thought to himself, how might I get over there?

Over the winter months and into early spring, Humphrey taught himself how to fish, how to go clamming and gather oysters, and discovered the best places to go beachcombing for shells and other seashore treasures. On clear days, the water sparkled like a million diamonds, porpoises jumped playfully out of the water, orca whales swam by in their pods chasing salmon, and eagles flew in high in circles above the island.

One day during the following summer, Humphrey was strolling the beach and spied a canoe that had washed ashore after a storm. In the canoe was an oar. Humphrey pulled it up onto the beach and covered it with ferns and branches so no one would see it. That night, under a full moon where the phosphorescence in the water glowed mysteriously, Humphrey left his Sasquatch lair and pulled the canoe out and into the water.

He paddled quietly toward Herron Island. It was not that far away, and on this still moonlit night he could easily find his way. After paddling across Case Inlet Humphrey came ashore by the oyster bay. He could see lights up above in some cabins and he avoided those because he was on another mission. Although he was well fed by the clams, oysters, cutthroat trout and salmon that he caught, he greatly desired hot dogs and Diet Cokes.

So he pulled his canoe up onto the south beach and made his way quietly toward a darkened cabin. When he was at the research lab Humphrey had taught himself how to pick locks. Being extremely dexterous, this was not hard at all, so he had a simple plan to pick the lock of a darkened cabin and see what kind of goodies he could find.

In one of the cabins he found exactly what he was looking for in the freezer: a pack of hot dogs. Taking a pillow case off of a pillow in the cabin bedroom, he threw those in, along with some buns and Doritos and Diet Cokes. Content with what he had, he carefully closed the door, being sure not to leave anything amiss, and headed back to McMicken Island.

As fall approached word started getting around Herron Island about a mysterious thief who had a particular hankering for hot dogs and Diet Coke. Other food items went missing too, including candy bars, nuts, chips, and sparkling water. Yet no one was able to identify the mystery thief. Humphrey liked to keep it that way. He only went on moonless nights and by cover of total darkness, where he could see just fine but humans could not. He knew where the dogs were and stayed away from them. He liked the deer and made a special effort to find treats for them, so carrots and bananas and apples would go missing as well.

As the days grew shorter Humphrey prepared his lair for the coming winter storms. He was quite comfortable. One night he paddled over to Herron Island looking for some winter clothes that he had spied on a couple previous cabin searches. It was getting cold and he wanted to make sure to stay warm in the coming months.

He paddled over earlier than normal, right before sunset, because few people were on the island in the fall and it was much quieter. He pulled his canoe up on the beach and began making his way up the trail to the cabin he had in mind. It was a nice little cabin with red trim and a green door and a friendly family with nice friends that he had spied on a few times during his evening adventures. Once, he saw a couple of boys pitch a tent outside the cabin with their father, and he watched them for a very, very, very long time from his hidden spot in the huckleberry bushes.

Drs. Gottlieb, Rottweiler, Dewey, Cheatham and Howe had come out to Herron Island for a Thanksgiving vacation. Their research project was completed. Unfortunately their grant funding had finally run out and they needed new sponsors. So they contacted a friend on the island with a rental cabin and decided to have a mini retreat while they plotted their next research effort. They thought orangutans might be receptive to their research efforts and were in the process of acquiring one who was exceptionally intelligent by the name of Jojo.

Out for a walk on the island one fine evening, they decided to go down to the lower deck of the friendly family nearby. They knew the family well since the mother and father had both worked at the world famous Battelle Memorial Institute in Seattle, were well renowned for their outstanding research and writing skills, and their daughter was the most beautiful, intelligent and precocious girl on the island.

Talk on the lower deck turned to Humphrey. It had been almost a year and all of them missed Humphrey greatly. “So sad,” said Dr. Rottweiler, recalling her lunch long ago with Humphrey. She missed him the most. Drs. Dewey, Cheatham and Howe recollected some of Humphrey’s amazing skills. In fact, they had followed his stock picking closely and made a fair amount of money off the monkey. And of course Dr. Gottlieb pondered his little friend’s fate, hoping that he had somehow prevailed after leaving them on that dark, miserable night.

As the sun set into a glorious palette of deep blue, red, pink and yellow skies over the calm waters of Case Inlet, Humphrey moved silently up the trail. Then he heard distinct, familiar voices. He stopped cold in his tracks when he heard Dr. Gottlieb’s voice, saying “I wish I could hug Humphrey right now.” He approached quietly, overhearing their conversation, recalling what good researchers they were, and how good they had been to him. He moved closer, and then, when conversation paused for a moment, he walked onto the deck and sat himself down at the picnic table.

They gasped as one. “Humphrey!,” exclaimed Dr. Dewey. “How are you, old boy? You look fantastic!” Each spoke out in unison and Humphrey gave them all the biggest grin he could muster.

Once the excitement had settled down a bit, they all sat back down again in a circle on the deck watching the sun finally set over McMicken Island. Dr. Rottweiler stared lovingly at Humphrey, walked over, sat down and put her arm around his shoulder.

Taking in the glorious sunset, happy to be reunited with his research team, looking proudly upon his island home across the water, Humphrey turned to her. He gazed lovingly in her eyes, then said in his very best Bogart imitation, “Hey baby, how you doin’? I’m fine.”

Maybe Humphrey wasn’t such an unlucky monkey, after all.

The END

Valentina

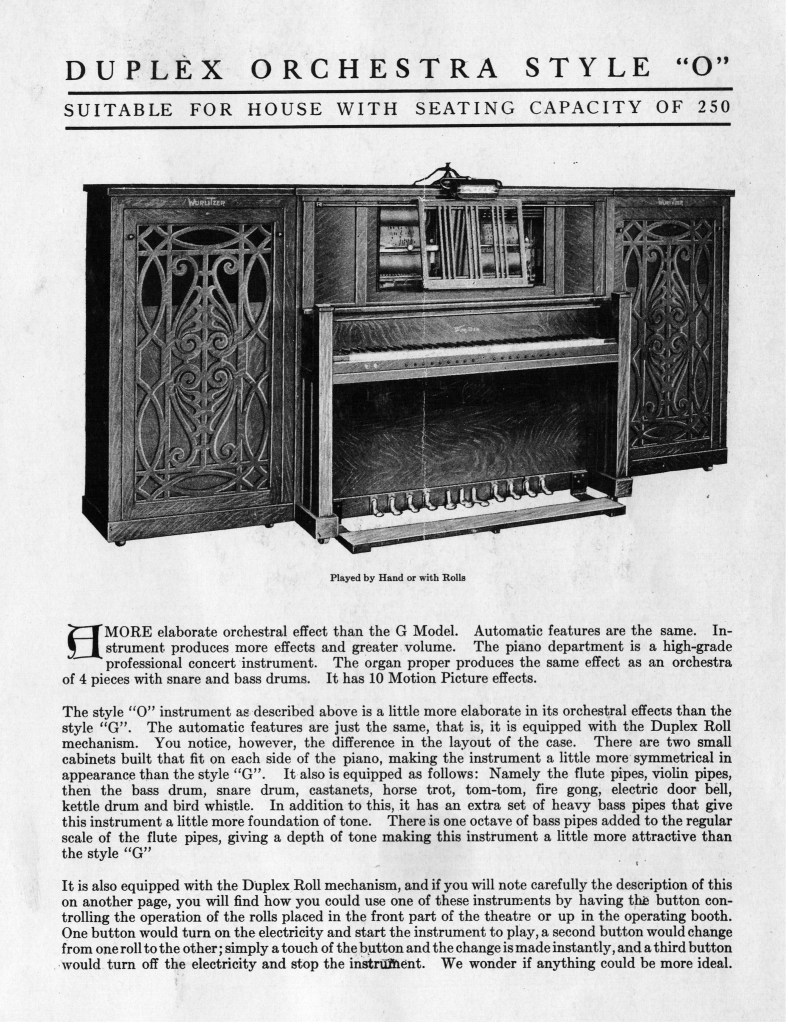

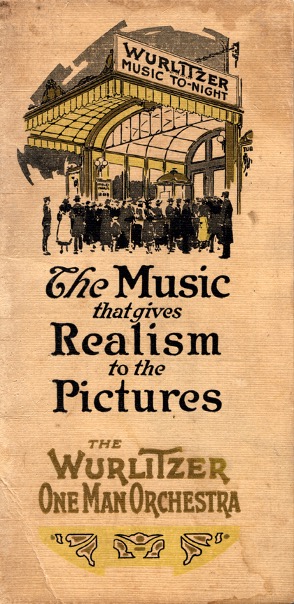

A labor of love underscores Larry Hibbard’s passion for Valentina, a 1919 Wurlitzer Model O photoplayer recently taking up long term residence at Chelan’s own Ruby Theatre. There Valentina reposes in all her glory on her hydraulic lift below the stage, waiting patiently for her next performance while her suitor attends diligently to her pneumatic, electronic and mechanical needs.

A photoplayer is a musical contraption that is beguiling in its simplicity and complexity. A player piano on steroids, a photoplayer relies on paper rolls of music that can automatically enliven a silent movie or alternatively be operated by a piano player at the keys.

The Maestro at his Machine

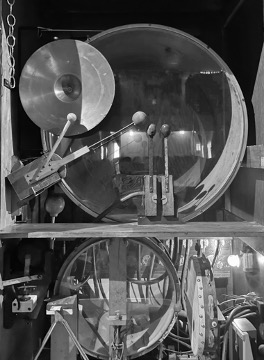

To add even more cacophony to the silent film adventures unfolding on the screen, photoplayers are equipped literally with all kinds of bells and whistles. Our interest of course is in Valentina, who comes quite capably equipped with a full piano keyboard, a percussion section in a cabinet to the left of the piano, four ranks of wooden pipes in a cabinet to the right, a set of bells under the keyboard, and various sound effects operated by buttons, pedals, and switches. Brilliant potential.

A performer sitting at the keys can add to the movie silently playing on the screen above with all sorts of percussion, wind instruments, and of course bells and whistles to perhaps underscore a chase scene, train robbery, or romantic scene. After viewing one such photoplayer maestro on You Tube, Joe Rinaudo, it’s questionable which is more interesting to watch, the now not so silent movie on the screen or the person behind the piano bench, hands pulling and pushing knobs and levers, feet jumping all over the pedals, giving the Wizard of Oz a run for his money.[1]

Enter Valentina

Larry Hibbard and Valentina

We were treated to one such impromptu performance at the museum’s 2023 annual meeting. At the event Larry Hibbard, owner of the Ruby Theatre and Valentina’s caretaker, raised Valentina on stage with a hydraulic lift that he designed and installed at the theater during the COVID pandemic. Once raised, she sits patiently as Larry carefully energizes Valentina. Under his loving care – much more orchestrated than just flipping a switch – she begins breathing through various air tubes that power and control the 88 piano keys, the bells below the keyboard, the flute pipes, violin pipes, bass drum, snare drum, castanets, horse trot, tom-tom, fire gong, electric doorbell, kettle drum, and bird whistle. A rank of wooden bass pipes provide additional depth of sound.

Valentina Keyboard with Pneumatic Tubes and Valves

Thus prepared, Larry engages the drive for the paper roll and an old time song begins playing. Off to the races we go, with Larry demonstrating the bells and whistles with gusto and verve. The audience laughs with delight and we are taken back to a time one hundred years ago when a silent movie would be accompanied by a Valentina and a Larry Hibbard at the keyboard.

Valentina Percussion Instruments

Valentina, like the Sony Walkman, eight track cassette decks, phonograph records, and my father’s 1976 Oldsmobile Toronado,[2] suffered the inevitable vicissitudes of technological progress when silent movies became talkies. In their heyday, “approximately 8,000 to 10,000 photoplayers were produced during the boom era of silent films, between 1910 and 1928. The popularity of the photoplayer sharply declined in the late 1920s as silent films were replaced by sound films, and few machines still exist today.”[3]

Wurlitzer Photoplayer Advertisement

Valentina Joins the Ruby Theatre

Larry purchased the Ruby Theatre in 1989; the 2014 History Notes article by Larry details the acquisition and subsequent restoration efforts to modernize the theater while preserving its unique standing as one of the oldest remaining movie theaters in the Pacific Northwest and the nation. Larry’s vision for preserving the Ruby and Valentina is evident in the care he and his wife, Mary Murphy, have put into the theatre to provide theatre patrons an authentic historic movie theatre experience.

Larry is uniquely qualified: a long term resident of the Chelan valley, an architect by training and profession, and a former orchardist who became adept at solving problems with orchard equipment. A tinkerer by avocation, Larry is skilled at fixing things and, when he can’t, finding friends who can assist and of course help others do the same.

Valentina requires such skills. With over 400 air valves, any leak will disable the machinery. Larry has replaced multiple valves and tubing. With his architectural vision and practical skills, Larry’s unique combination of experience and talents suit Valentina and the Ruby well.

Valentina had a predecessor at the Ruby. In 1922 the Ruby acquired an American Fotoplayer – a different brand of photoplayer than Valentina – which was played by Dorothy Peterson. She referred to it as an organ; its fate is unknown. By the late 1920’s “talkies” replaced the silent movies, and photoplayers became obsolete.

Valentina was manufactured by Wurlitzer in New York in 1919, a century before Larry acquired her. She subsequently headed south to Tennessee in 1920, Chicago in the 1950s, South Carolina in the 1970s where she was rebuilt, and ultimately ended up in Kirkland, Washington. Larry found her, brought Valentina back to Chelan, and began the long restoration process through trial, error and ingenuity.

After acquiring Valentina in 2019 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Larry designed a hydraulic lift and retractable stage floor for Valentina. He then constructed the platform with the assistance of many others locally, an amazing feat of engineering in itself. The hydraulic lift allows Larry to raise Valentina from her residence beneath the stage on a separate platform until her performance begins. Truly a dramatic entrance that builds audience excitement and anticipation.

An Authentic Chelan Treasure

Larry’s goal is to preserve the character of the Ruby, returning the theater to what it was, photoplayer and all, a 109 year old theater with original silent movies and music. His goal is to build a sense of community and preserve a very unique historic movie house and photoplayer.

How unique? According to Larry, Valentina, all 1,400 pounds of her, is one of a few known Wurlitzer photoplayers of its kind in operation. Larry estimates there may be only 18 to 24 working photoplayers of all makes remaining worldwide. He knows of only one person doing full restoration who lives in Gold Beach, Oregon. A person in Florida repairs valves. Despite her rarity, Valentina has been brought back to life through Larry’s tinkering, trials, and hard work learning the intricacies of pneumatic tubes, valves, instruments, and parts.

This year, celebrating the Ruby’s 109th anniversary, Valentina rose to the occasion (literally) from the piano pit for a mini concert before being lowered to accompany the century old silent movies on screen. Today, Valentina’s future, under the care of her beau Larry, is bright.

A Photoplayer Renaissance?

On a somewhat heretical closing note, would it not be wonderful to acquire a musical paper roll of a classic rock song, say, Stairway to Heaven by Led Zeppelin, accompanied by a raucous musical performance by Valentina and Larry? One can only hope. Or, as the original Wurlitzer description states, “We wonder if anything could be more ideal.”

Wurlitzer Photoplayer Catalog Cover

[1] Just google Joe Rinaudo. You won’t be disappointed.

[2] Some things of course should be consigned to obsolescence. Not Valentina.

[3] Photoplayer, from Wikipedia, accessed August 27, 2023, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photoplayer.

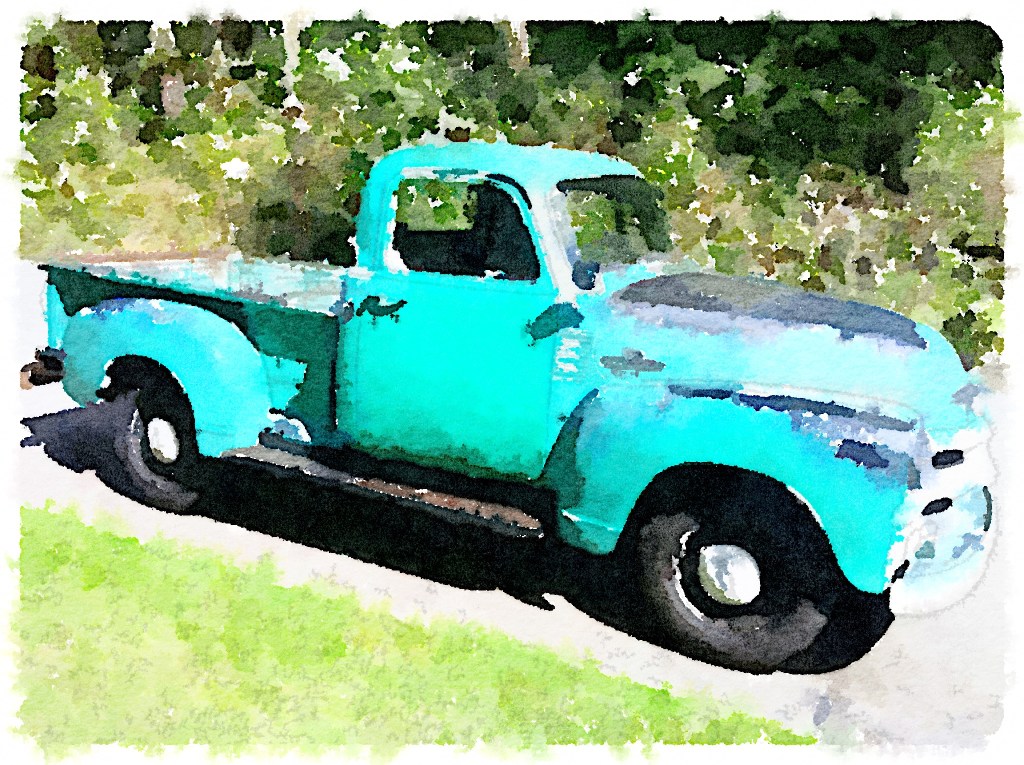

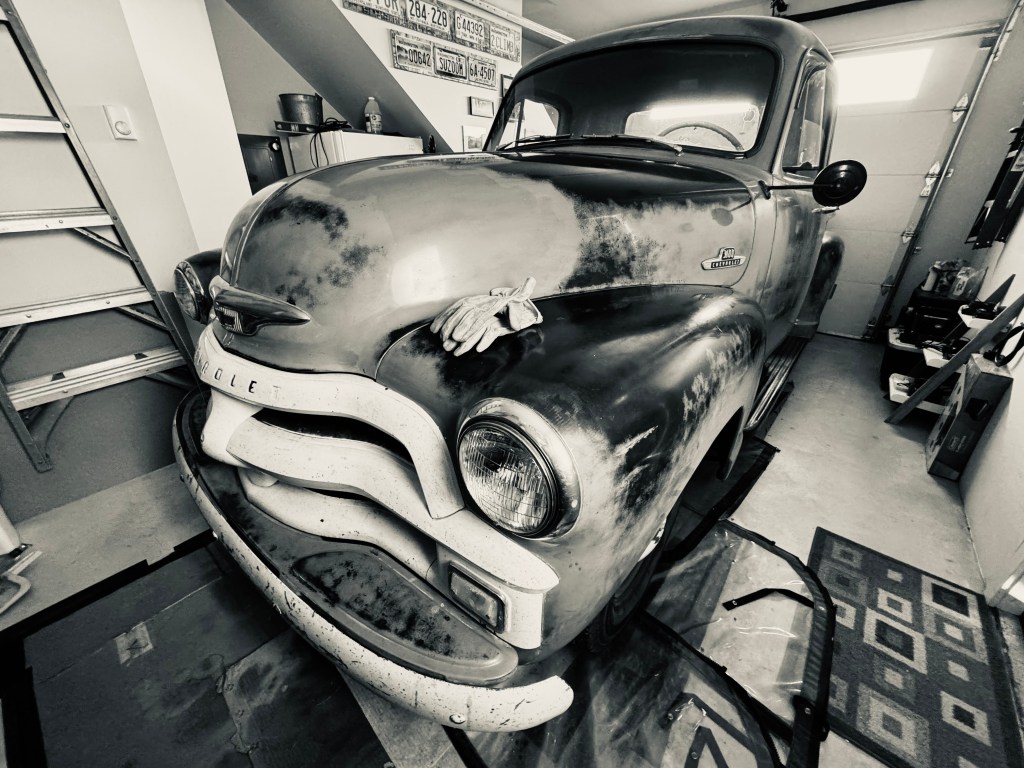

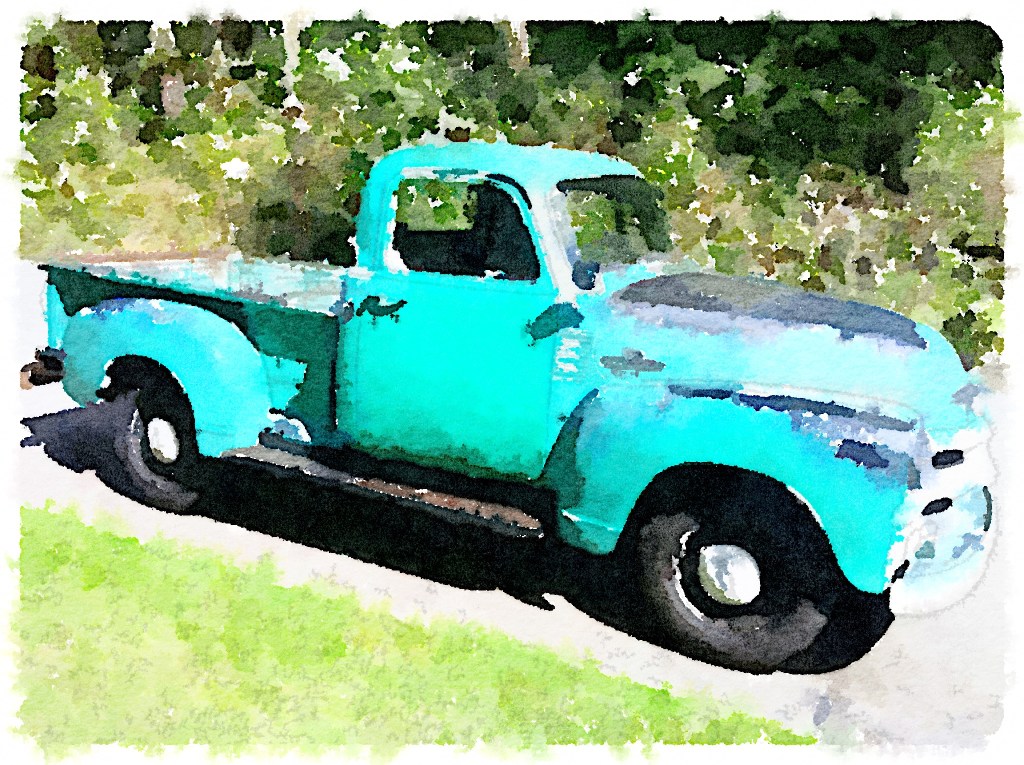

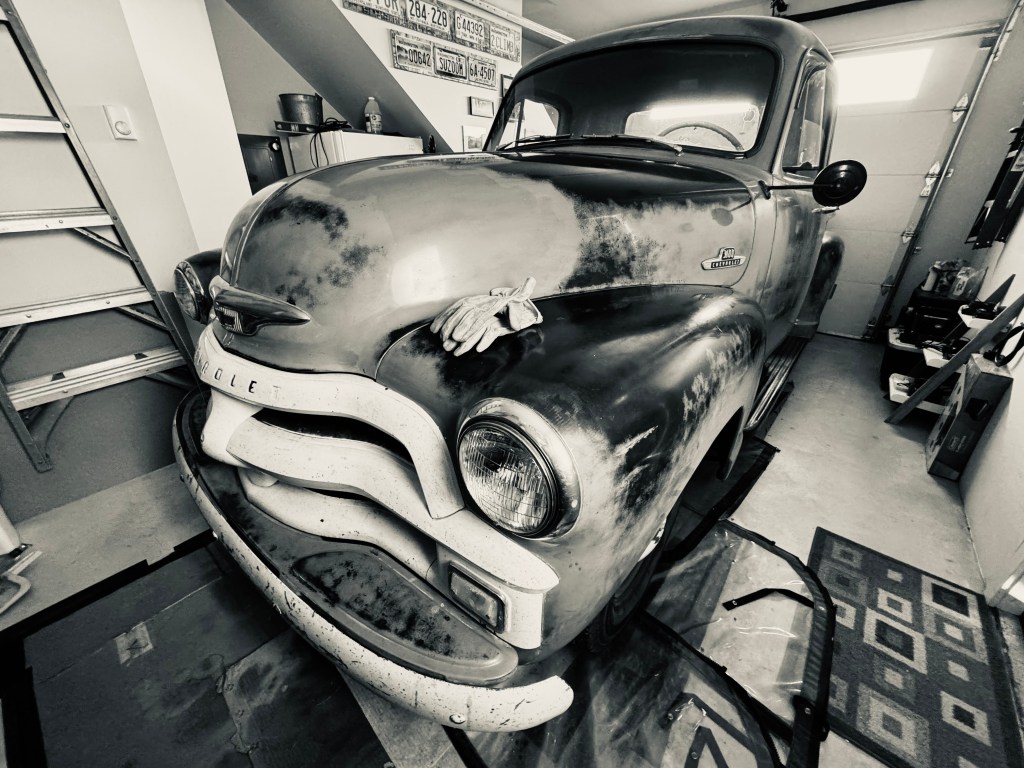

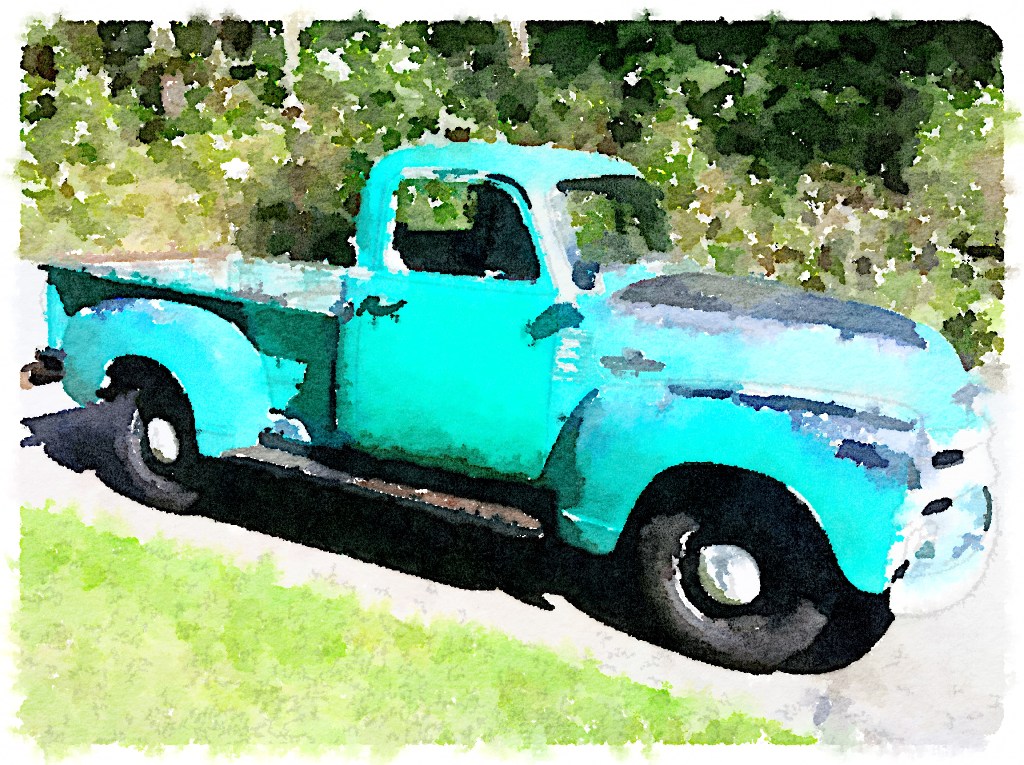

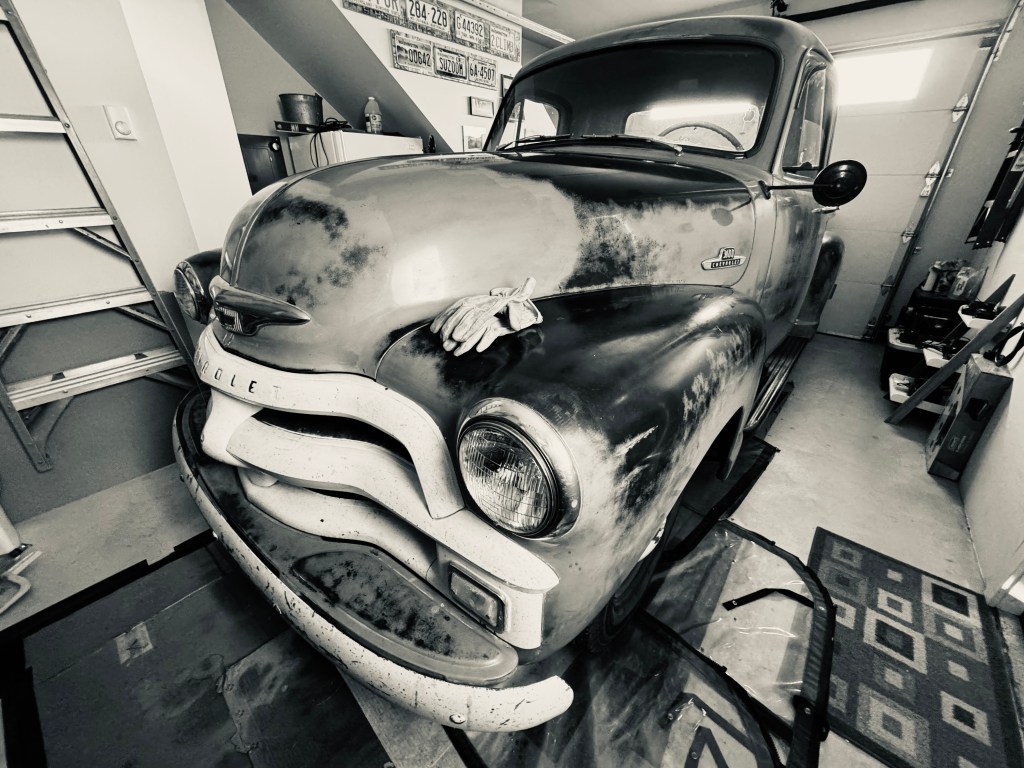

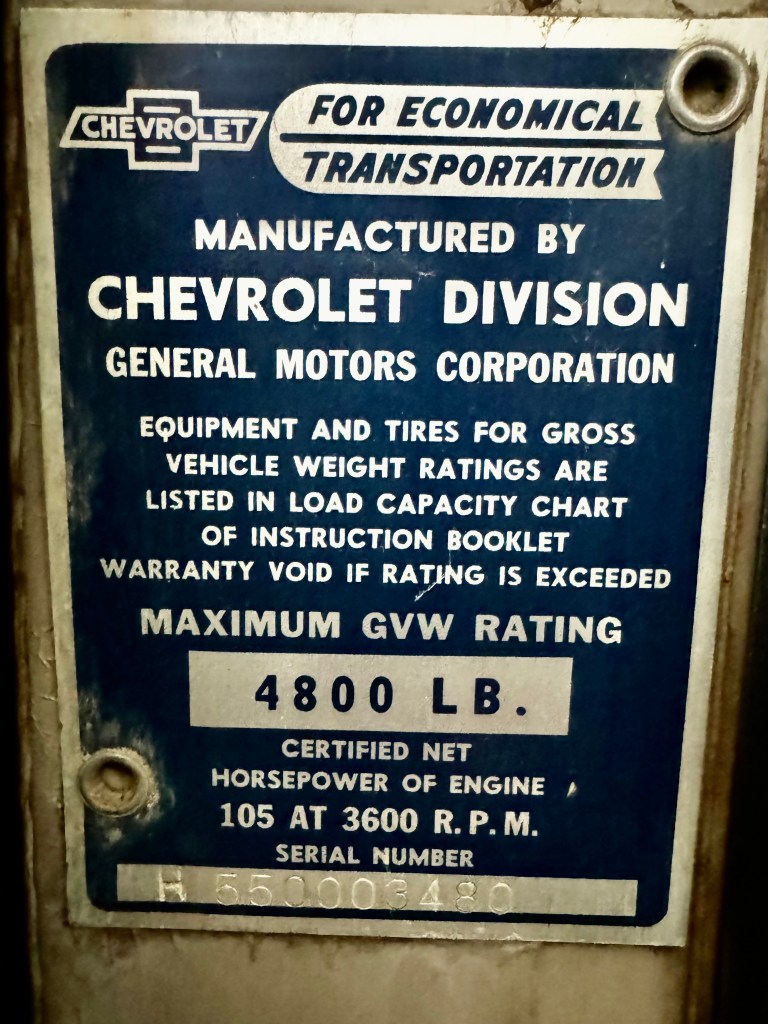

This is Mel, a 1955 Chevrolet 3100 series pickup. He is so named after my Uncle Merald who owned this truck in Pasco, Washington for many decades until I acquired him in 2010. Since none of the kids could pronounce let alone spell Merald, we just called him Uncle Mel. As a child I loved to climb all over the truck and pretend I was driving him in the garage when we would visit Uncle Mel and Aunt Bernie in Pasco during the holidays. It inspired a love of vehicles that I cherish to this day. This was his personal work truck. Mel.

As I was growing up I used to always ask Mel when he would sell the truck to me. He would smile and say, “I sold it to Matthew (his grandson and my godson) for a nickel.” Despite my offer to double the price, he graciously declined.

When Uncle Mel passed away in 2009, Aunt Bernie asked if I was still interested in the truck… We brought him back to Lake Forest Park and he’s been with us ever since. 75,000 original miles and going strong…

Details:

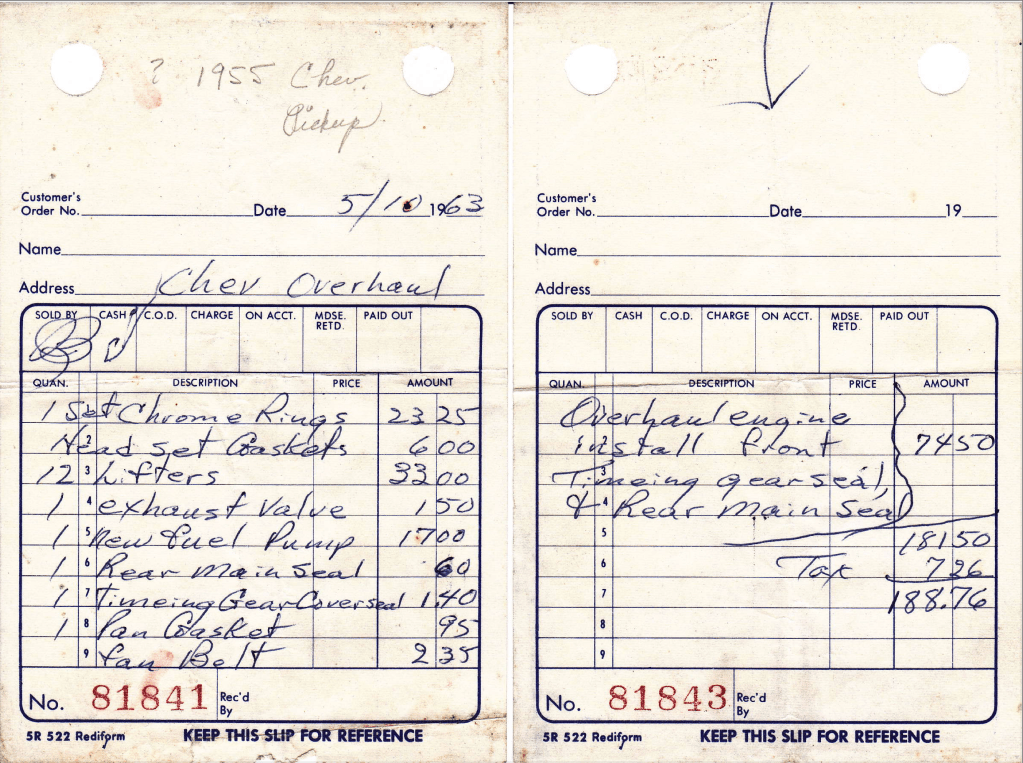

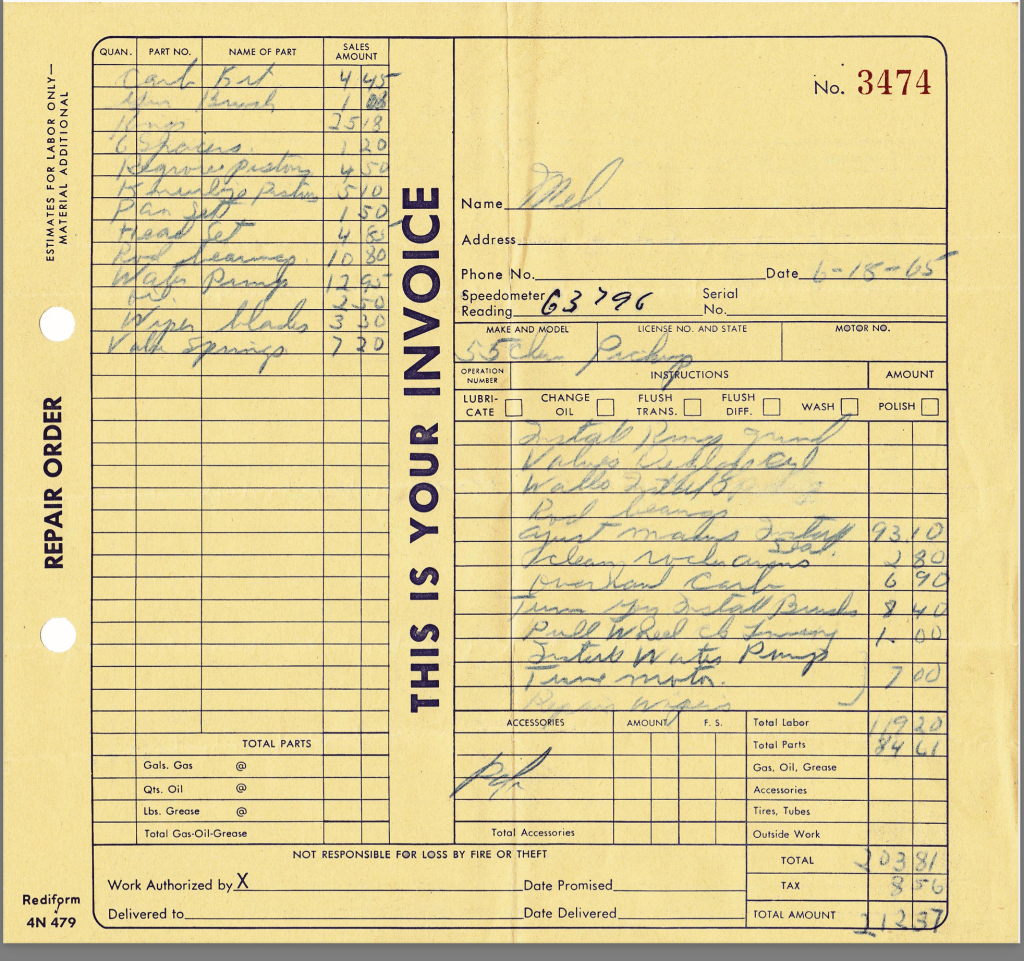

Engine rebuild receipts from 1963 and 1965:

Additional repairs:

This is a special truck with a great background. Of particular value is its originality, lack of rust in any meaningful sense for a vehicle of this age (mostly garaged its entire life in dry eastern Washington), and a family history dating back to Uncle Mel’s purchase in 1958. (You can even see the chalk marks on the engine firewall during manufacturing indicating optional automatic transmission and mirrors.) Today Mel enjoys exploring the orchards and vineyards around the Chelan Valley.

Sometimes historic preservation runs through the Chelan Valley in theatrical ways. In November 2021 Larry Hibbard and Mary Murphy, owners of the 110-year-old Ruby Theatre, reached out to Dr. Wendy Waszut-Barrett concerning the Ruby’s old, dilapidated theatre curtains. Wendy is an international expert in painted theatre scenery restoration and replication at Historic Stage Services in Minnesota. They were particularly interested in Wendy’s interest and availability to replicate the Ruby’s main drape, complete with hand-painted borders.[i] As luck would have it, their interests coincided with Okanogan’s historic Hub Theater gaining national attention when the owners of their 115-year-old building discovered two 60-foot long murals hidden behind plaster during renovations.[ii]

In 2022 Wendy traveled to north central Washington to meet with both theatre owners and upon returning to Minnesota contracted with Liba Fabrics in New York City to create the new draperies for the Ruby, funded in part with a grant from the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. [iii] In 2023 Historic Stage Services shipped the new plain curtains, valance and side curtains to the Ruby Theatre where they were installed for permanent display.

In April 2024 Wendy traveled from her studio in Minnesota to the Ruby Theatre to paint the draperies. Prior to her departure she replicated the original stencils on the curtains and made several samples to examine on site. Local volunteers, including Patrece Canoy-Barrett and Luke Roehl, assisted Wendy with painting and hanging the curtains. Wendy observed that the gold paint in the stencils “reflects light beautifully, especially in low-light conditions.”[iv]

Wendy Waszut-Barrett stenciling the curtains. Courtesy: Larry Hibbard.

A Second Act

During the 1920s it was common for theatre curtains to feature hand-painted advertisements. Advertising curtains were a way for local businesses to promote their products and services to theatre patrons. Advertising curtains served a dual purpose: they were both functional and a source of revenue for the theatres.[v]

In 1919 Henrietta “Babe” Kelsey Hendershott’s father, R. L. Kelsey, took over managing the theatre and later took ownership. The Kelsey family lived in a two room “apartment” behind the screen for several years. [vi]

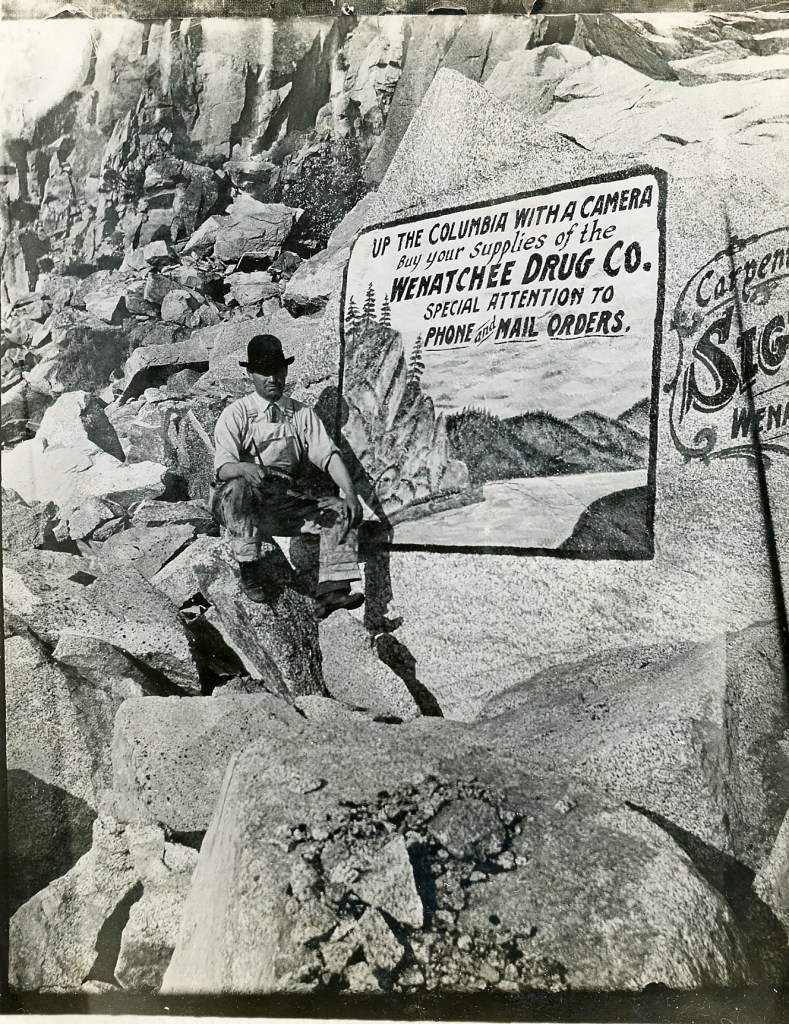

During the frigid depths of the Great Depression, the Chelan Mirror reported on New Year’s Eve, 1931, that Joe Carpenter, a Wenatchee commercial sign painter, was painting a new advertising curtain for the Ruby Theatre. [vii] The center picture shows the high bluffs above Moore’s point, with surrounding advertisements. Babe Hendershott helped Joe Carpenter paint the screen and sold ads on the curtain to local businesses.

Joe Carpenter sign painting, possibly Earthquake Point of Ribbon Cliff. Courtesy: Lake Chelan Historical Society.

Chelan Mirror article on painting the new advertising curtain by Joe Carpenter, December 31st, 1931. Courtesy: Lake Chelan Historical Society.

As older theatres modernized, the need for advertising curtains diminished and in 1976 Babe Hendershott donated the advertising curtain to the museum for preservation and display.[viii] During the curtain restoration in April 2024 volunteers moved the advertising curtain from the museum to the Ruby Theatre to temporarily display the advertising curtain in its glory.

Moving the advertising curtain from the Museum to the Ruby Theatre for display, April 2024. Courtesy: Dr. Wendy Waszut-Barrett.

On April 25th, 2024, Wendy presented the newly restored curtains, complete with the hanging advertising curtain. She provided historical context and background with illuminating details on curtain restoration, the dry pigment painting process, and her passion to preserve and celebrate the theatrical heritage, extant scenery conservation, and training artists in distemper painting techniques for the stage.

The advertising curtain painted by Joe Carpenter hanging at the Ruby Theatre, April 2024. Courtesy: Larry Hibbard.

Curtains Take a Curtain Call

The Ruby Theatre now celebrates the new stenciled curtains and the repainted proscenium arch. As to the advertising curtain painted by Joe Carpenter, the museum and Ruby Theatre are exploring options to hang the curtain at the Ruby Theatre once again.

Next time while enjoying a movie at the Ruby take a moment to appreciate the new hand-painted stenciled curtains and newly painted proscenium arch. And of course, drop by the museum to see the advertising curtain on display. Be sure to read the curtain ads and, as always, shop locally.

A promising encore performance is ahead.

[i] Wendy Waszut-Barrett. May 6, 2024. “Travels of a Scenic Artist and Scholar: Ruby Theatre. Chelan, Washington, April 22-29, 2024”, https://drypigment.net/2024/05/06/travels-of-a-scenic-artist-and-scholar-ruby-theatre-chelan-washington-april-22-29-2024/, accessed August 3, 2024.

[ii] Sara Smart. January 27, 2022. “A couple renovating a 115-year-old building discovered two 60-foot-long hidden murals. CNN, https://www.cnn.com/style/article/couple-discover-murals-during-renovation-trnd/index.html, accessed August 3, 2024.

[iii] Grant funding provided by Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. The project was supported in part by a grant from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

[iv] Wendy Waszut-Barrett. 2024. Ibid.

[v] Wendy Waszut-Barrett. 2024. Ibid.

[vi] Jon Nuxoll. April 8, 1992. “Life upon the (Ruby Theater) stage”, Chelan Mirror.

[vii] Dennis King. March 16, 2024. “Up the Columbia with a Camera – Wenatchee Drug Company – Joe Carpenter painted signs on rocks possibly Earthquake Point of Ribbon Cliff”, https://www.facebook.com/groups/997976200763883/?multi_permalinks=1528366801058151&hoisted_section_header_type=recently_seen, accessed August 3, 2024.

[viii] According to Larry Hibbard, the advertising curtain was removed from the theatre before 1947 and most likely replaced in the late 1930s with another advertising curtain.